Australian Story / By Susan Chenery and Jennifer Feller

Professor Veena Sahajwalla says waste is an "opportunity just waiting to be harnessed". Skeeps a collection of rubbish in her house. Her car is full of garbage that she takes to work. She gets excited at landfill dumps; at all the good stuff she finds.

"She's obsessed with waste," says her husband, Rama Mahapatra. But it is not waste to her, even if she is known as the Waste Queen. Professor Sahajwalla is a revolutionary, an inventor who sees rubbish as an opportunity.

"Waste is really one of those untapped resources just waiting to be harnessed," she says. “it's time to be "bold and brave" to tackle Australia's mounting waste issues.”

Professor Sahajwalla is Director of the UNSW Sydney SMaRT Centre and a Eureka Prize winner, the Oscars of the science world in Australia. She was awarded the PLuS Alliance prize for innovation in 2017. She is a whirlwind of ideas and energy, determined to tackle the mountain of waste generated by Australians’ every year. “All those unwanted things, all the 67 million tonnes of waste that go into landfill in Australia every year are bringing us to a tipping point — "a waste crisis".

"For far too long everyone just assumed we could just use stuff and throw it away," she says. But we can't just keep digging bigger and bigger holes for landfill”. The tiles that have been made from discarded textiles are the result of years of experimentation at UNSW have been dubbed 'green ceramics

Late last year, Australia took a step towards addressing the effects of the "waste crisis", passing legislation banning the export of unprocessed waste overseas. Professor Sahajwalla says now is the time to address new ways of re-purposing our waste. "We can no longer assume that we'll pack it off and send it somewhere overseas and it then becomes somebody else's problem," she says. "To put it quite bluntly, we're going to have to take responsibility for our own stuff."

Professor Sahajwalla's eye is always on the future. Her innovative thinking has led to the idea of "green ceramics" — products made from technology that is set to revolutionise manufacturing and the way we furnish our homes.

She can see a world where instead of cutting marble from mountains in Italy, people can use tiles made from glass bottles combined with second-hand clothes to tile bathrooms and kitchens. The "designer-look" tiles and furnishings have been installed in a new apartment to show the possibilities of green ceramics.(Supplied: Mirvac)

The 'caffeinated problem solver'

Fuelled by coffee and the bananas she carries in her handbag, Professor Sahajwalla is a ball of energy, driven, tireless, constantly taking calls — as anyone who finds themselves in her gravitational pull will discover — rotting out possible solutions to the problems thrown at her.

It is a process that takes her from rubbish dumps to science labs to manufacturing plants and corporate boardrooms. "She completely steps out of the box to solve the problem," her husband says. If we can use re-purposed waste materials instead of taking mineral resources out of the ground it is, Professor Sahajwalla says, "a double-whammy and a slam dunk".

Source: ABC War on Waste |

"People were too reliant on traditional coal and coke, no one was really looking at alternatives," she says. She called it green steel and millions of old tyres have since been diverted from landfill. It was this success that launched her as a scientist superstar, recognised globally.

"It is a once in a 100-year revolution the way in which steel is made," said Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering CEO Kylie Walker. "Her invention was groundbreaking."

Since then, Professor Sahajwalla has taken the idea of re-purposing waste further and further; from steel mills into people's homes.

Because when it came to chucking things out, she says: "We need to be bold and brave and think big."

A CSIRO report released in January revealed that Australia could add $1 billion to its annual GDP by switching to an economy that focuses on re-purposing waste materials.

A childhood of recycling in action

Professor Sahajwalla grew up in Mumbai, where many people still did not have the luxury of being able to buy new things. "There is no such thing as waste; everything had a value, and everything had potential," she says.

As a kid she would walk around the streets seeing recycling in action.

"I'd see people working, repairing shoes, guys carting stuff around like television sets, all kinds of heavy things on their heads that they might have picked up," she says.

"Even today there is a big part of the economy that operates off repairing things. It was fascinating for me.

"It is really what inspired me to take on engineering as a field of study."

Her father was a civil engineer, her mother a paediatrician who travelled long distances on public transport to go to work.

"My mother continues to be an amazing role model," Professor Sahajwalla says.

"For her anything is possible. Do what you love but do it at your very best and be your best."

Professor Sahajwalla was a studious child, encouraged "to be curious about things" preferring studying at home to going out with friends.

She was the only woman in her metallurgy class at the Indian Institute of Technology. "I was probably quite unusual in pursuing my love for science and engineering. That was OK because I was quite comfortable in my shoes."

On average, every Australian use 53 kilograms of plastic a year. It's one of the issues Professor Sahajwalla hopes can be curbed in the future.(Australian Story: Jennifer Feller)

Isolating though it was, she graduated top of her class. "Some of the male colleagues, I'm sure, were not entirely delighted," she says.

Professor Sahajwalla met her husband in Vancouver, where they were both studying metallurgical engineering at the University of British Columbia. Back then, her relentless recycling verged on being problematic.

"There was a potential clash because I was absolutely a clean freak," he remembers. "But she was kind of a little bit messy because she just wanted to keep reusing things and I wanted to throw things out."

When she finished her PhD, Professor Sahajwalla followed her now-husband to Australia. "I started my career here with CSIRO and eventually came to UNSW."

There she began working on what would become green steel.

The next generation, she says, will hopefully eliminate coal from the process of making steel.

Textile recycling

Textile recycling may give a new life to clothes that can't be donated to charity. So, what is it and how can you recycle your old clothes?

In 2005, Professor Sahajwalla won the Eureka prize, the pinnacle of scientific achievement in Australia. It would be just one of many awards in Australia and overseas.

Now she was able to get the funding to help start the UNSW Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) where she and a team of 30 passionate young engineers and scientists started their research experimenting with waste materials.

"Keeping up with Veena is the challenge," says Anirban Ghose, an engineer who has worked with her for five years. "It's from one idea to the next. She's a caffeinated problem solver.

"We've had these mad trips where we've gone to India for two-and-a-half weeks and visited 11 different cities and she has been presenting every day."

Manufacturing partner - Mirvac

The splashback (top photo) is made from 'green ceramics' which come from the unlikely combination of re-purposed glass and textiles.(Supplied: Mirvac)

Every year tonnes of clothes get thrown away along with mountains of glass. After years of experimenting, Professor Sahajwalla and her team have combined textiles and glass to produce tiles — coined "green ceramics"— that "have this amazing designer-type look".

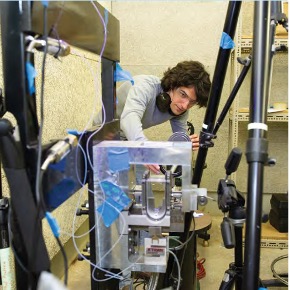

Now they have designed a series of machines, named a "micro factory", that can be used outside the lab to produce similar products.

"We are reimagining what manufacturing could look like in the future," she says.

After years of reaching out to the building industry, in 2019 Professor Sahajwalla finally received a call from construction giant Mirvac, which could see the potential in her idea.

Mattress recycler Andrew Douglas had looked around the world for solutions to his mattress waste when he met Veena.

National residential marketing director Natasha Ryko says the building and construction industry contributes 60 per cent of waste in Australia which equates to about 41 million tonnes a year. "We needed to come up with a sustainability initiative for a particular project," she says.

Professor Sahajwalla and her team were commissioned to make a dining table using waste glass and textile and a side table made from corflute banners collected on campus.

Then she was asked to work on their latest development and something much more ambitious.

"We've now actually put in another range and it's gone into flooring, walling applications, and really all kinds of very creative applications," she says

She said seeing the products in a real-world setting was a "goosebumps moment".

"We have never seen anything like what Veena has been doing," Mirvac CEO and managing director Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz says. "It is really pioneering. We were just blown away."

Re-imagining manufacturing

Professor Sahajwalla's mother was right. For her daughter, anything was possible.

Now, she is launching the first commercially operating "micro factory" in one of the rural communities, where she thinks a big part of its future lies.

As production begins in a small shed at Cootamundra, NSW, Professor Sahajwalla can see her vision being realised. After eight years of trials and research it was an emotional moment when she flicked the switch to get it running earlier this month.

"A moment," she says, "of fear and wonder. It's the first step but a very big one."

The micro factory is operated by Andrew Douglas, a long-time collaborator, who was running a small recycling business looking for ways to recycle old mattresses and tyres when they met.

"I've been on a global search looking for a solution for mattress waste and Veena's idea to develop a micro factory and look at proper end use for the textile was like nothing I'd seen before, so I was very keen to get involved," he says.

Professor Sahajwalla hopes the micro factory model will be adopted across Australia, particularly in the regions, to deal with all kinds of problematic waste.

She is confident Australia can achieve a "zero-waste economy".

"When we start to see a future where people are going out and asking for resources and materials that come from waste streams then I think we would see that we are at the cusp of that change," she says.

© Australian Story - Edited from ABC Net article published on 22nd February 2021